What will things looks like in ten years? This is the existential question this newsletter exists to answer — at least when it comes to education and schools.

I was watching an interview with Jeff Bezos, CEO of Amazon. He got asked this question and answered it with a counter-question of his own: what is NOT going to change? This got me thinking about the constants in education, and how all the media noise around Covid-19 is distracting us from what really matters.

Parents will always want academic schools.

No parent ever says, 'I wish my child knew less.'

Start afresh. Build back better. Re-tool learning for 21st century learners. Re-think the paradigm. It's tempting rhetoric, but do we risk throwing the baby out with the bathwater? Parents – regardless of whether they are in the state or independent sector – will still want academic schools that enable their children to become capable, successful adults. With the explosion of the global middle class, this translates in practice to schools helping their leavers to access high-quality university courses via terminal assessments such as A Levels or the International Baccalaureate.

In the UK we are unusual in having high-stakes public exams at 16 and 18. The GCSE was originally invented as an exit point for less academically inclined pupils to leave compulsory education and move into the trade/industrial workforce. There have been a lot of calls to scrap the GCSE now that education in the UK is compulsory up to age 18. A few schools might be as brave as Bedales, who have heeded that call and ditching GCSEs in all but the very core subjects, but these will be few and far between. Therefore, I predict that in UK independent schools the thinking on academics will be evolution rather than revolution. I won't be able to spin a TED talk out of this, but my prediction is surely more realistic...

Parents will always seek out schools which help their child win, whatever system is in place.

No parent ever says, 'I wish my child could have got lower grades.'

There will, however, be a shift on which grades schools emphasise. Many independent schools will probably start opting out of GCSE league tables, as they could be perceived as a distraction from the real work of driving up A Level performance. Private schools will invest even more in entrance counselling for the top global universities. (Oxbridge still counts, but it isn't the be-all-and-end-all any more.)

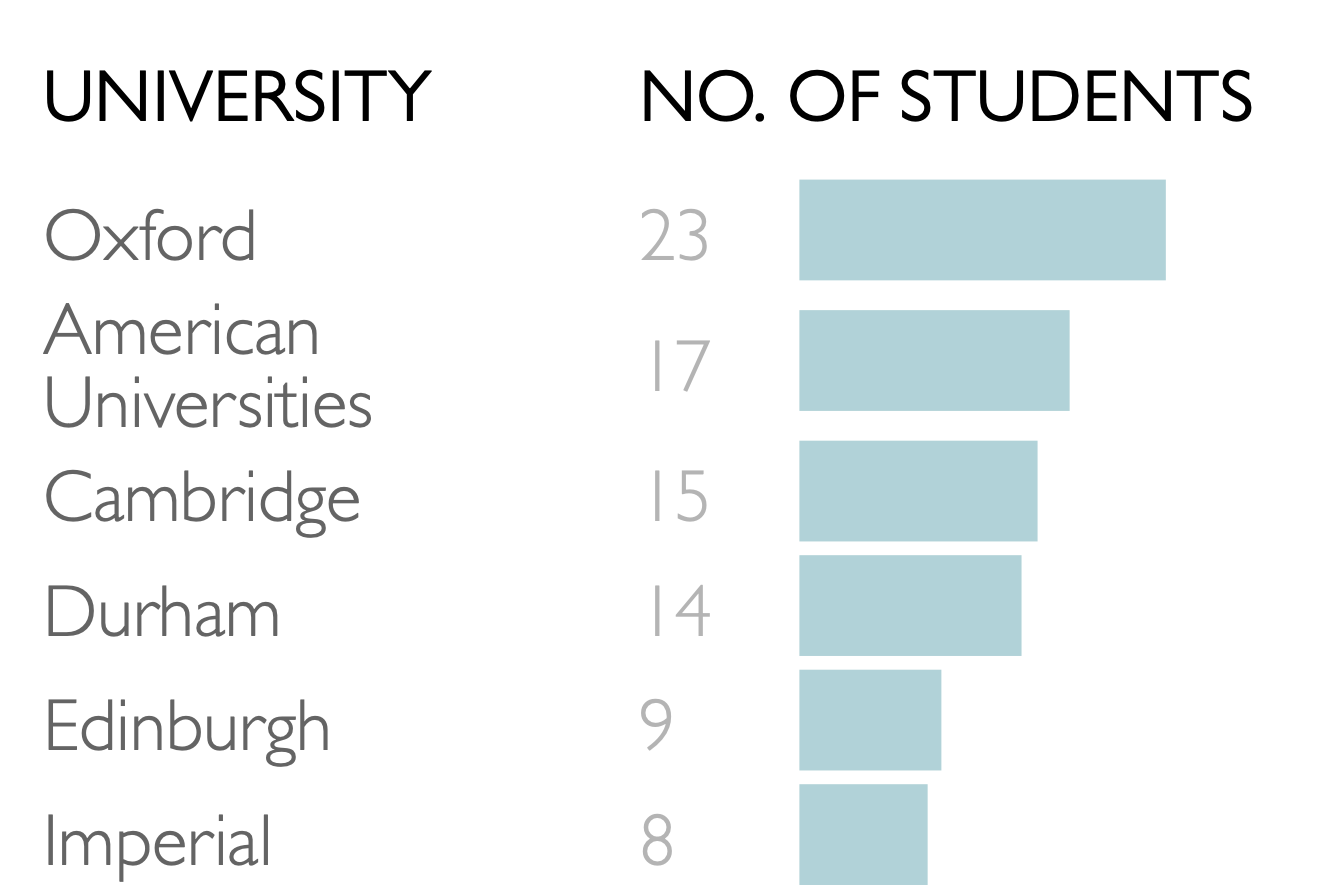

Tuition fees at UK universities for British students were raised to £9000 in September 2012, following the Browne Review of Higher Education. This has driven more sixth formers to look abroad, especially the USA, where renowned institutions are delighted to give generous scholarships to British students. Here is last year's leavers' data from a high-achieving academic school in London:

Universities are already setting their own admissions tests for competitive subjects such as medicine, law, economics and history. Following last year's debacle with Centre Assessed Grades for GCSEs and A Levels, we will almost certainly see more of this stand-alone approach to assessment, as universities' confidence in the robustness of Government sanctioned public exams evaporates.

Parents paying fees will always want schools which are 'better' than the state.

No parent at an independent school ever says, 'I wish my child's school was worse than the state option.'

Primary education has been transformed in the UK over recent years. When the state can deliver ambitious academic teaching for free, supported by high-quality online lessons (look at Oak National Academy), parents will rightly look at private prep schools and wonder where their £5-6k a term is going. This is already happening. Alpha Plus, a group which operates mainly prep schools in London with high fee levels, is millions in the red.

And if exams are scaled back, the traditional 'reason to buy' of independent senior schools – exam results – at £20k+ per year is strained, especially in a time of economic uncertainty. Schools will start to specialise more. Lots of schools are already taking steps to define their USP more tightly, and adapt their admissions procedures to recruit pupils aligned with their specific mission. Here are some examples:

St Edward's Oxford: 'Teddies' is pursuing exactly the path of evolution rather than revolution that I think will define academics within the independent sector, pulling back slightly from GCSE mania in Years 10-11, and launching in-house Pathways vocational courses, and Perspectives critical thinking/humanities courses.

Millfield has very successfully specialised its USP around sporting performance, enabling it to be perceived as a 'prestige' boarding school, attractive to high-flying global families, while remaining academically non-selective in its intake.

Apex2100: this is an overtly specialised winter sports school, supported by the United Learning schools group, in the Alpine ski resort of Tignes. It is founded by Sir Clive Woodward, former England rugby coach, to nurture the next generation of Winter Olympic talent.

St James Schools in London have integrated Eastern and Western spiritual traditions and mindfulness into their teaching and pastoral care, with a holistic approach called Personal Mastery.

Parents will always want bricks and mortar schools because education is still about human connections.

No parent says, 'I wish my child could spend all day with no friends, staring at an iPad.'

Honestly: do you really your child doing online school for ever?

No, I didn't think so…

There has certainly been a significant growth in online schools during the pandemic but I cannot foresee this becoming mainstream in the long-term. It is fantastic that online schools exist as part of the educational mix in this country, and they are valuable for some children, especially those with mental health problems or additional learning needs for whom mainstream schooling can be overwhelming.

But let's get real: you cannot leave your child at alone all day. So once we are unlocked and start working from the office again, online school only works if one parent can commit to being at home full-time, thus effectively taking us back to pre-war Britain, where one parent will be chained the iPad instead of the dishes or the mangle. Furthermore, social learning, pastoral care and co-curricular provision are all much, much weaker in an online environment. No parent ever says, 'I wish my child's school looked after them less' or, 'I wish my child had fewer friends'.